The World's Columbian Exposition 1893

The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 was the first World's Fair to be held at Chicago (the second

one was the Century of Progress Exhibition of 1933). It celebrated

the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' arrival in the New World in 1492. The iconic centerpiece of

the Fair, the large water pool, represented the long voyage Columbus took to the New World. Chicago bested

New York City; Washington, D.C.; and St. Louis for the honor of hosting the fair. The Exposition was an

influential social and cultural event and had a profound effect on architecture, sanitation, the arts,

Chicago's self-image, and American industrial optimism.

one was the Century of Progress Exhibition of 1933). It celebrated

the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' arrival in the New World in 1492. The iconic centerpiece of

the Fair, the large water pool, represented the long voyage Columbus took to the New World. Chicago bested

New York City; Washington, D.C.; and St. Louis for the honor of hosting the fair. The Exposition was an

influential social and cultural event and had a profound effect on architecture, sanitation, the arts,

Chicago's self-image, and American industrial optimism.

The layout of the Chicago Columbian Exposition was, in large part, designed by Daniel Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted. It was the prototype of what Burnham and his colleagues thought a city should be. It was designed to follow Beaux Arts principles of design, namely French neoclassical architecture principles based on symmetry, balance, and splendor. Many prominent architects designed its 14 "great buildings". Artists and musicians were featured in exhibits and many also made depictions and works of art inspired of the exposition.

The fair ended with the city in shock, as popular mayor Carter Harrison, Sr. was assassinated by Patrick Eugene Prendergast two days before the fair's closing. Closing ceremonies were canceled in favor of a public memorial service.

On the medallic side, the fair generated an inordinate number of coins, medals, plaques and memorabilia. The most famous medal was the prize medal designed by America's greatest medallic sculptor of the day: Augustus St. Gaudens. St. Gaudens had been awarded the contract to design the prize medal to show that American medals could artistically hold their own against European medals. At the time, it was widely acknowledged that the medals designed by the U.S. Mint were artistically uninspiring and lacking appeal when compared to the best medallic works from the European continent. St. Gaudens was regarded as the country's best chance to prove that American art could compete at the same level.

This did not sit well with Charles E. Barber, the Chief Engraver at the U.S. Mint. He had wanted the contract for this medal awarded to the Mint. Barber saw his chance when the design for the prize medal's reverse was leaked early. As it turned out, St. Gaudens had included a nude boy on the reverse, something that was quite common on European medals but very unusual in American art. Pressure mounted to force St. Gaudens to redesign the reverse to make it less explicit. He resisted at first but then gave in and started working on a redesign. In the meantime though, Barber had used his government contacts to lobby for the reverse being awarded to the U.S. Mint. The controversy between the two sides kept the country entertained for several years.

Through some very underhanded and shady dealings on the part of Barber's supporters St. Gaudens lost the battle and, to add insult to injury, Barber himself got to design the reverse for St. Gauden's Columbian Fair medal. St. Gaudens had pushed the limits and the establishment had fought back and defeated him. It was undoubtedly a great injustice that was committed against him but it should not have come totally unexpected. American morality of the day was not yet ready for European Beaux Arts designs.

Click on the Medals tab to see some of the medals issued for this exposition.

Click or tap the medals to see their reverse sides.

The obverse bears nude Columbia seated on winged car, holding palm frond in outstretched left and resting right on cornucopia; on left, rising sun over clouds; on right, clouds. At left above sun, 1892; signed at right with artist's letter V.

The reverse bears dedication: TO / Martin Roche / ONE OF THE DESIGNERS / OF THE WORLD'S / COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION / ON THE FOURHUNDREDTH / ANNIVERSARY / OF THE LANDING OF / COLUMBUS / OCTOBER 21 / 1892

Martin Roche was part owner of the famous architectural firm of "Holabird and Roche", one of the most prolific firms in Chicago. They are known for the Marquette Building, the neo-classical Soldier Field and the New South Wales Building of the Columbian Exposition. The firm was renamed after William Holabird and Martin Roche died and is now known as "Holabird and Root."

Elihu Vedder is famous and well known for his paintings, in particular his illustrations for "The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam." He is less well known for his medallic work but this medal is a beautiful and rare example of his skill as a sculptor.

The medal measures 64mm in diameter and was struck in bronze by the Whiting Manufacturing Company of New York.

References:

This medal was issued to commemorate the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago 1893.

The obverse bears bust of Columbus left. Around to left and right, CHRISTOPHER - COLUMBUS; signed under truncated arm, LEA AHLBORN

The reverse bears a Spanish explorer in full armor holding sword and flag on left, facing two natives on right; ships anchored in background. In exergue, CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS LANDING AND / TAKING POSSESSION OF THE ISLAND / WHICH HE NAMED SAN SALVADOR / OCT. 12TH 1492; signed at bottom left, LEA AHLBORN

The medal measures 51mm in diameter and was struck by the Royal Swedish Mint in bronze.

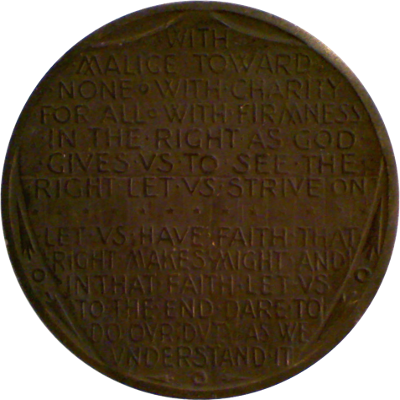

This medal's obverse bears bust of younger, unbearded Lincoln right. Around, 1809 ★ ABRAHAM ★★ LINCOLN ★ 1865; signed over shoulder at left, Zearing

The reverse bears excerpts from Lincoln's second inaugural address at top and his Cooper Union address at bottom. The excerpts are: WITH / MALICE TOWARD / NONE ⚪ WITH CHARITY / FOR ALL ⚪ WITH FIRMNESS / IN THE RIGHT AS GOD / GIVES VS TO SEE THE / RIGHT LET VS STRIVE ON / (thirteen stars) / LET VS HAVE FAITH THAT / RIGHT MAKES MIGHT AND / IN THAT FAITH LET VS / TO THE END DARE TO / DO OVR DVTY AS WE / VNDERSTAND IT

The two quotations on the reverse are taken from two of Lincoln's famous speeches. The first quotation is from the end of his second inaugural address on March 4th, 1865. The second quotation is from his February 27, 1860 address at the Cooper Union in New York.

This was one of many medals created for the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago.

The medal measures 48mm and was struck in silver, bronze, gilt, copper, brass, aluminum and white metal.

References: King 504, Eglit 85

Contact me if you have links that might merit inclusion on this page.